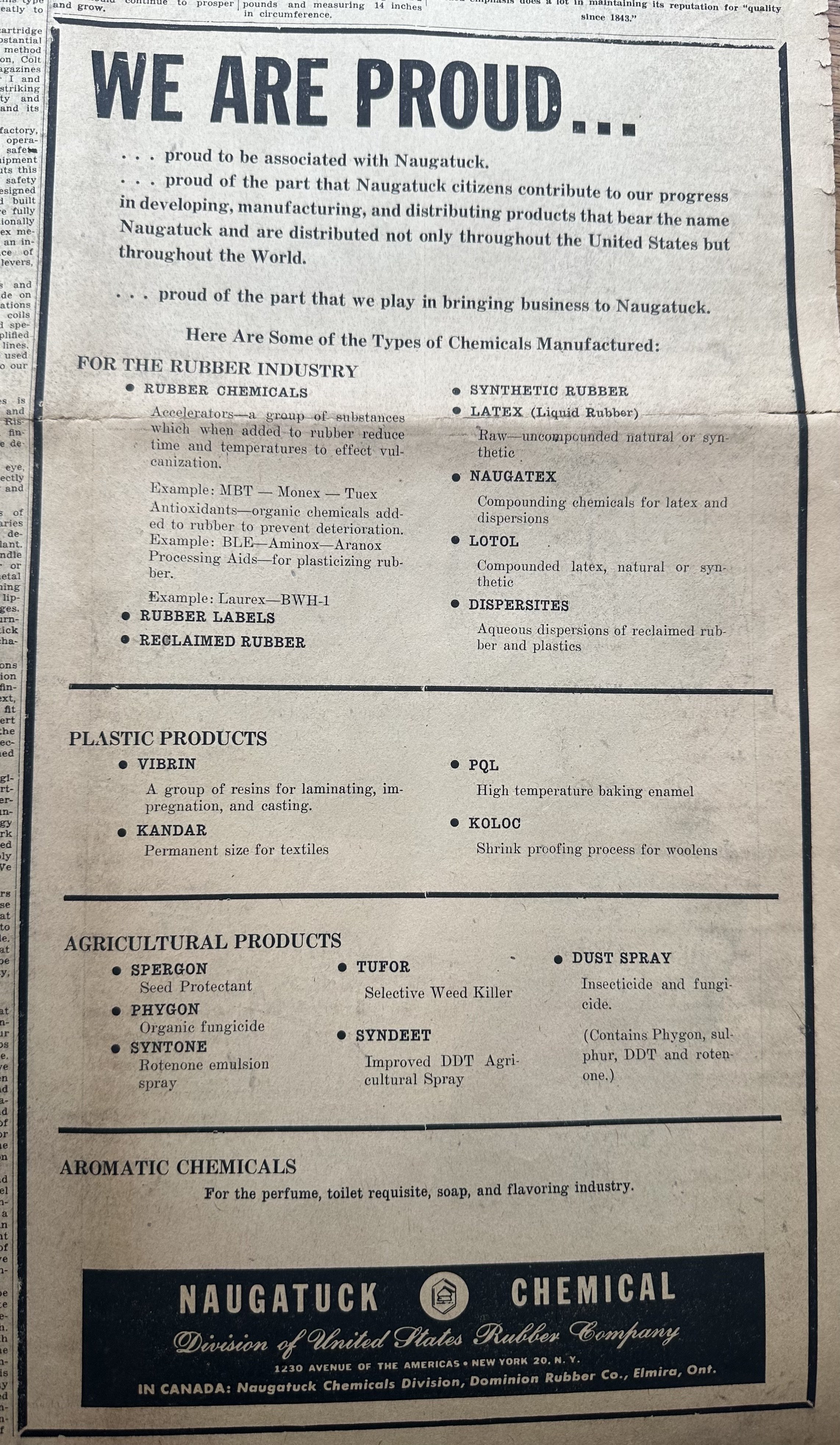

Naugatuck Chemical Division

Excerpt from Naugatuck Daily News – Saturday, August 31, 1946

World War II - History Edition

Synthetic Division Turned Out 181,000,000 Pounds Of Rubber Vital To War Program

Reclaiming Plant Processed An Additional 360,000,000 Pounds Of Rubber

Ninety five per cent of the wide variety of processes and products of the Naugatuck Chemical and Synthetic rubber plants were vital to victory in World War II.

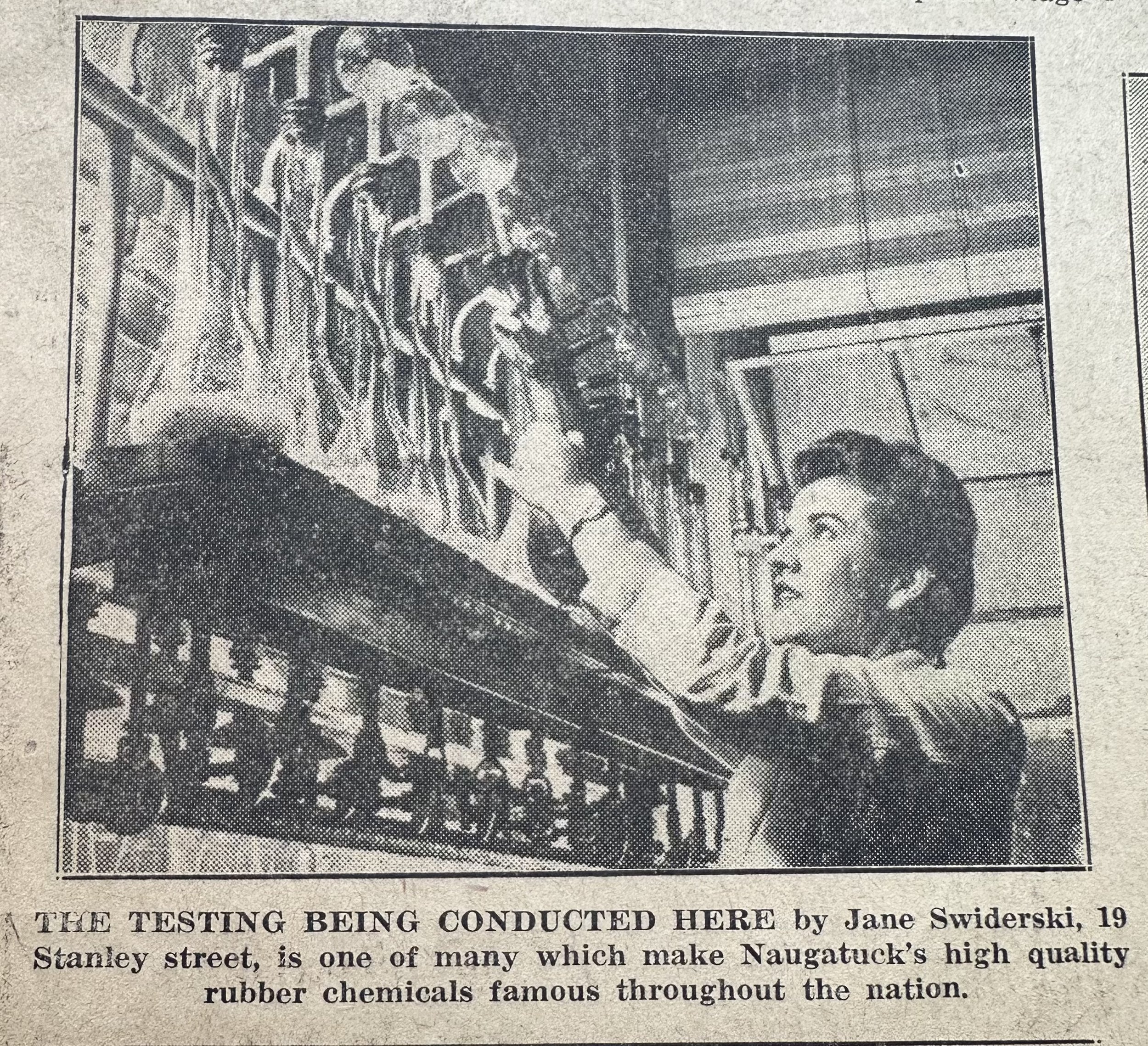

The results of the 1500 men and women who worked in these plants were not measured in headlines but in tons of raw materials that filled vital needs in a tremendously complex industrial war effort.

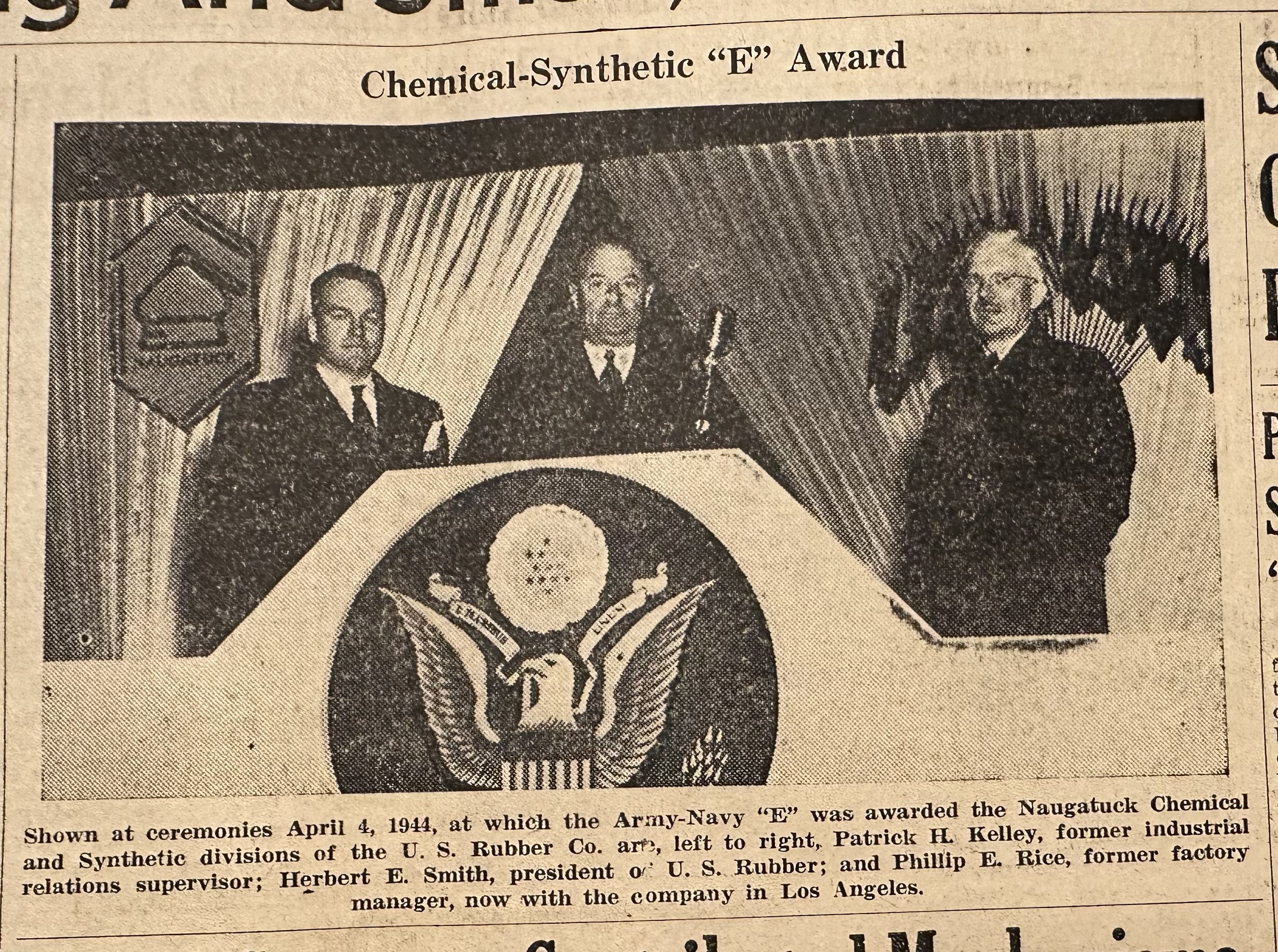

The United States government recognized the value of this work with three Army-Navy “E” awards presented jointly to the personnel of the two plants.

Presentation of the first of these awards was made on April 4, 1944 at a ceremony attended by more than 3,000 persons from Naugatuck and its environs. At that time, Herbert E. Smith, president of the United States Rubber Company, summarized the work of the two plants in a brief address:

“You people of Naugatuck Chemical,” Mr. Smith said, “occupy a special place in the United States Rubber family. Other divisions and other plants make rubber products. You produce the chemical ingredients which are necessary for the manufacture of all rubber goods—to make them last longer and do a better job.”

“By the nature of your work, you have been privileged to take part in an unusual degree in the many phases of our national rubber program.”

“Before the war, our Government wisely decided to build up a stock pile of rubber in this country. In this early and far-sighted move, you played a most important part. You built large underground concrete tanks for the storage of that most precious and useful of all forms of rubber—concentrated liquid latex. When war broke out, your pool of latex was the largest in the country. You acted as agent for Rubber Reserve Company in conserving the Nation’s stores of latex and in their distribution for essential military needs. This was a valuable service.” You manufactured reclaimed rubber in quantities and qualities never before achieved. Reclaimed rubber and dispersions were necessary to replace and to extend the supplies of new rubber during the critical period following the loss of our plantations.

“When our company decided to undertake the manufacture of synthetic rubber, you people of Naugatuck were selected to do that job. You built and operated a pioneer pilot plant. You were making synthetic rubber here as early as 1940. Thanks to this early experience, you were chosen to build and operate one of the first Government plants.

“You have established new techniques for processing synthetic rubber. You have developed and manufactured many of the chemicals necessary for converting this new raw material of industry into useful products.

“Through your work in chemicals, reclaimed rubber and synthetic rubber, you have helped to save our Nation from the military and civilian collapse which threatened two years ago.

“Few people back of the front lines have had the privilege of serving their country more directly and in a more important way than you men and women of the Chemical and Synthetic rubber plants here at Naugatuck. Our company is proud of you. On behalf of the officers and directors I extend to each of you our sincerest appreciation and heartiest congratulations.”

Although located in an area where there was a critical shortage of man-power, the two Naugatuck plants were able to meet the repeatedly increased demands of war because every man increased his efficiency.

At the synthetic plant operated for the government, 350 people produced 181,000,000 pounds of synthetic rubber during the war years. This meant that each man produced approximately 517,000 pounds of rubber.

Even more significant was the intensified research in the development of new synthetic rubbers and the improvement of existing types. A total of 98 new varieties were developed by scientists of the development department.

One of the most prominent was non-discoloring GR-S, with more than 2,400,000 pounds being produced in 1945. Another non-discoloring synthetic was developed for the manufacture of soles and heels. Progress was made in the development of a much better processing GR-S for footwear, insulated wire, extruded mechanical goods, and foam rubber. Resin soap rubbers, developed for better processing and higher quality in tires, received widespread recognition and use.

During the war years, 71,330,000 pounds of rubber chemicals were produced. These rubber chemicals filled an important need in the processing of nearly 30,000 rubber products for war. These products ranged from the mammoth fuel cells of the B-29’s that bombed Tokyo to the smallest stopper on a bottle of blood plasma.

Rubber reclaimed at the Naugatuck chemical plant helped to bridge the gap from the loss of natural rubber plantations in the Far East until GR-S synthetic rubber was in large-scale production. In the four war years from 1941 through 1945, some 250 people in the reclaiming plant processed 360,000,000 pounds of rubber. This meant that each man produced more than 1,400,000 pounds.

Because of the restrictions in the use of crude rubber, it became necessary to substitute a synthetic material called Vinylite in the manufacture of Army raincoats, in Signal Corps covering material and in other coated fabrics. Vinylite itself, however was a critical material and very expensive. Naugatuck Chemical developed an exclusive process for reclaiming Vinylite. This process made use of available equipment. Work was started on a plant to carry out this undertaking in September, 1942. The first delivery of reclaimed Vinylite was made in December, 1942, and the total shipments of this material to June 1, 1944, amounted to 1,309,000 pounds.

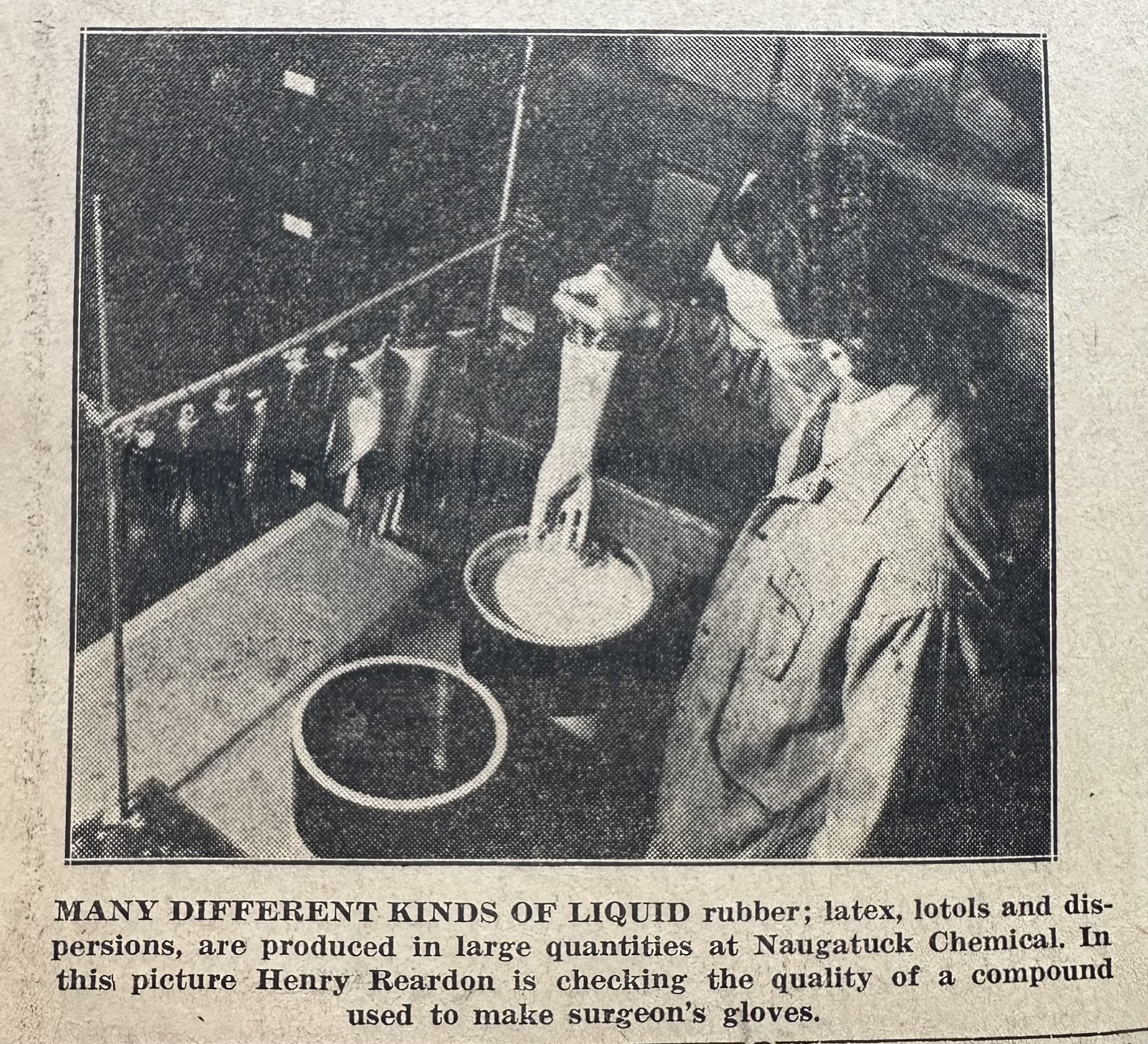

Dispersions, which are suspensions or emulsions of rubber and rubber-like materials in water, were produced in large quantities at Naugatuck for war purposes. These water dispersed materials were widely used in the manufacture of Army and Navy footwear, wire and cable, protective coatings, the preparation of rayon tire cords, artificial leathers, brake linings, belting and packaging. In many war products, dispersions effectively replaced natural rubber latex which was one of the most critical war materials.

Methods developed for the manufacture of dispersions for special purposes led to the production of a road seam filler which was used in large quantities on fighter strips and bomber runways around the world.

Lotols, compounded rubber latices, produced at Naugatuck were used for insulating assault wire vital to combat communication on the fighting fronts of Europe and the Pacific.

Kotal, a strippable plastic coating for protecting planes during their shipment overseas on the decks of freighters and tankers, was the only coating of its type to meet all Army Air Forces specifications. Kotal was produced in large volume during 1945.

At the outset of the synthetic rubber program, the industry had trouble making a rubber which could be processed on existing mill machinery. Tough, unwieldy polymers could not be handled without redesigning mills and calendars.

The active interest and work of Naugatuck Chemical aided in the development of a chemical coded OEI, which was added to synthetic rubber during the polymerization process to produce a softer, more easily processed synthetic rubber. Consultation with leading scientists disclosed that this chemical was discovered in an obscure patent. However, no use was indicated for it, and further investigation revealed that no facilities for its production existed anywhere in the world.

Naugatuck Chemical developed the techniques necessary for its manufacture, and built the first plant for its large scale production. This plant expanded to produce 100,000 pounds of OEI monthly.

Naugatuck Chemical also designed and built at Naugatuck for the Defense Plant Corporation an additional OEI plant with a capacity of 250,000 pounds per month. This plant operated at 200 per cent rated capacity for the greater part of the war years.

The combined production of these two plants was almost 12,000,000 pounds of OEI. Without the early development and subsequent large scale production of OEI, the government synthetic rubber program would have been badly delayed.

Records were broken in critical materials affecting not only the rubber but other industries. Naugatuck Chemical produced sulphuric acid at 130 per cent rated capacity for neighboring metal industries which made important war goods. The agricultural chemical Spergon was produced at 200 per cent rated capacity for protecting the yield of food crops.

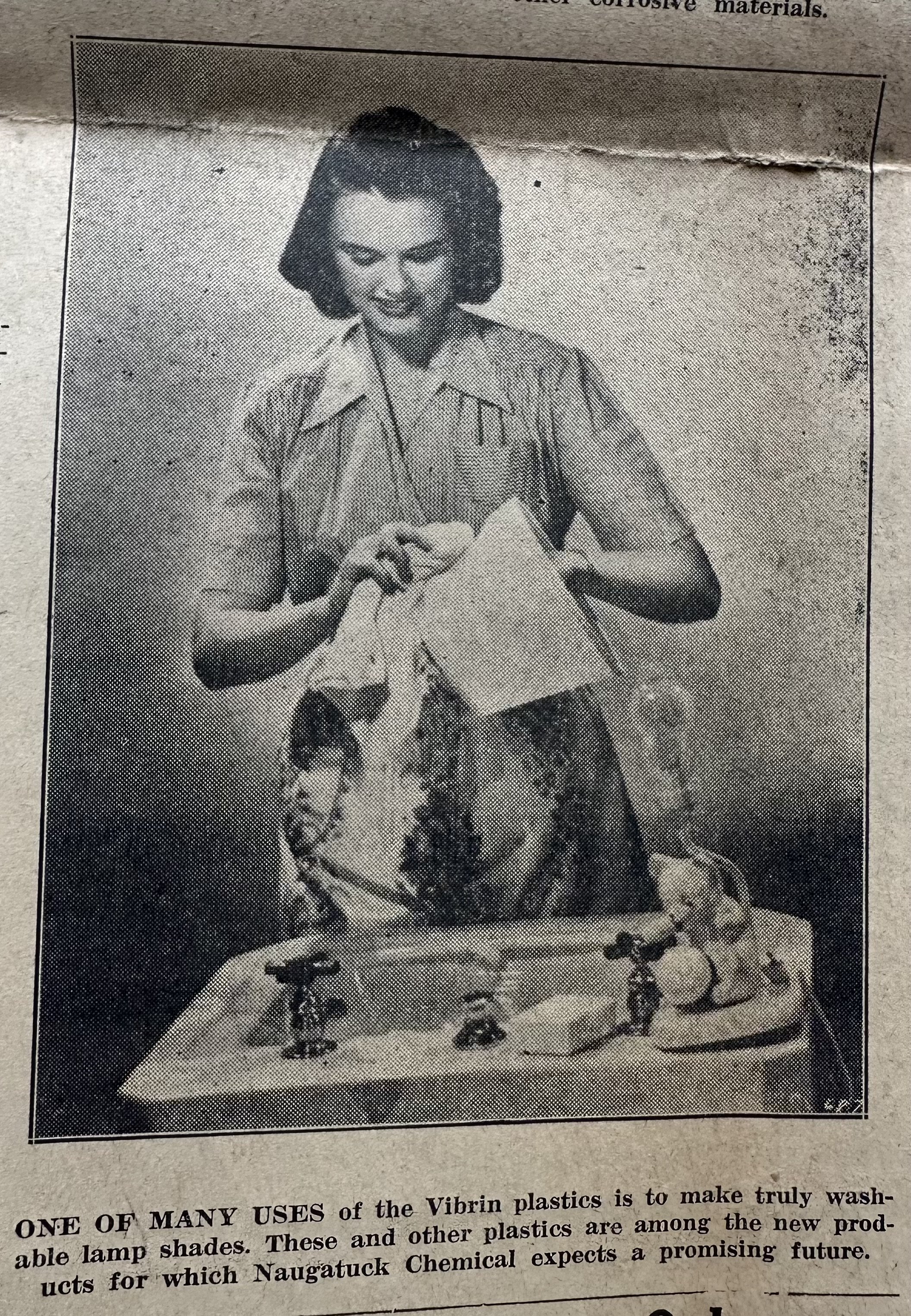

Notable among the new chemicals developed by the Naugatuck Chemical plant to fill a critical war need was Vibrin, a thermo-setting plastic.

Naugatuck Daily News – Saturday, August 31, 1946 World War II - History Edition

Naugatuck Daily News – Monday, September 15, 1947

Naugatuck Daily News – Monday, September 15, 1947

Naugatuck Daily News – Monday, September 15, 1947

Naugatuck Daily News – Monday, September 15, 1947

Naugatuck Daily News – Monday, September 15, 1947

Naugatuck Daily News – Monday, September 15, 1947

In the March–April 2008 issue of the Naugatuck Historical Society Newsletter, it was reported that the Naugatuck Chemical smokestacks were scheduled for demolition. However, the exact date of their removal was not specified in the newsletter. Based on available information, the smokestacks were likely taken down around that time, but a precise date is not confirmed.

Community Contribution

Who here doesn’t have great memories of strapping the prized Christmas tree onto the top of their experimental fiberglass-body roadster and speeding it home?

No? Anyone? Bueller?

Maybe that’s yet another stretch I’m making for the sake of this story, but there is no denying the automobile’s place in the traditions and pop culture surrounding the biggest holiday of the year. Our favorite Christmas movies all inevitably feature an iconic vehicle or two: https://www.hagerty.com/media/market-trends/christmas-movie-cars/ The Beach Boys re-imagined Santa’s sleigh as a souped-up hot rod...

It's the little Saint Nick (little Saint Nick)

Just a little bobsled we call the old Saint Nick

But she'll walk a toboggan with a four speed stick

She's candy apple red with a ski for a wheel

And when Santa hits the gas man just watch her peel…https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AbgxDgVmMF0

And a memory I am sure we all share is of the many rides in the family car packed with wrapped presents, on our way to visit our relatives for a delicious holiday meal and some festive family time together. Those are memories I hold especially dear in 2020, when many of us will remain quarantined at home, only able to visit our friends and family via a video chat or phone call.

The automobile meant an unprecedented new mobility for most Americans, and this country took to the personal car like no other, quickly becoming the number one producer and consumer of automobiles very shortly after Henry Ford began mass production in 1908. The automobile made it easier for us to get to work, and we could live farther away from those jobs, leading to the growth of our suburbs. The family car meant we could stay more connected to family who had moved away, we could run errands faster and farther, freeing up leisure time, and driving the car itself became a source of leisure. Enter the sports car.

Driving was always considered a thrill, since even the earliest attempts at powered locomotion. Ever since Karl Benz patented the first true, modern automobile, a three-wheeled motor car, known as the "Motorwagen," in 1886, humans have enjoyed a love affair with their cars and the open road. So it’s no surprise that in a town like Naugatuck, the world capital of the rubber industry, that cars were of major importance. So important in fact, that of course one of our most interesting “firsts” involves a sports car.

Dubbed the “Glasspar G2 Sports Car," the revolutionary new concept of an all fiberglass car body was constructed with none other than Naugatuck Chemical’s Vibrin Resin in 1952. Bill Tritt invented the Glasspar G2 in order to help his friend, United States Air Force Major Ken Brooks. Major Brooks needed a body for a customized "hot rod" he was building.

"There are various theories about the origin of the term "hot rod." The common theme is that "hot" related to "hotting up" a car, which means modifying it for greater performance. One theory is that "rod" means roadster, a lightweight 2-door car which was often used as the basis for early hot rods. Another theory is that "rod" refers to camshaft, a part of the engine which was often upgraded in order to increase power output. The predecessors to the hot rod were the modified cars used in the Prohibition era by bootleggers to evade revenue agents and other law enforcement. Hot rods first appeared in the late 1930s in southern California, where people raced modified cars on dry lake beds northeast of Los Angeles, under the rules of the Southern California Timing Association (SCTA). This gained popularity after World War II, because many returning soldiers, (like Major Ken Brooks) had received technical training. The first hot rods were old cars; most often Fords, typically 1910-20 Model Ts, 1928–31 Model As, or 1932-34 Model Bs, modified to reduce weight."

Major Brooks created his speedster using a stripped down Willys Jeep chassis and a highly modified V8 engine. Bill Tritt seemed like the man who could design a body for the one-of-a-kind vehicle. Tritt had become known for building small fiberglass boat hulls in his shop located in Costa Mesa, California. He convinced Brooks that fiberglass was an ideal material for the hot rod's body. The Glasspar G2 became the first production all-fiberglass sports car body built by an American fiberglass manufacturer, and Naugatuck made it happen.

In an interview about this pivotal meshing of fiberglass and sports car, Bill Tritt related the following:

"Ken Brooks was building a hot rod - something to go fast in and have fun. The first time I went for a ride in it, it was too exciting for me. It was a fast car, and had no floor or body yet. I just saw the ground rushing by. Ken was a wonderful mechanic but didn't have an eye for design, and the chassis and drivetrain were from the hot rod he was building. Ken was going to have the body built out of aluminum, which was going to be expensive. I was already building fiberglass boats, and convinced him that fiberglass would be durable and much more cost effective for a sports car body."

Unfortunately at the same time Tritt was convincing Major Brooks to let him build his fiberglass roadster, the Korean War was raging overseas. It became impossible to acquire the polyester resin needed for the fiberglass body. Through pure chance, the Naugatuck Chemical Company would end up saving a project happening 3,000 miles away from their hometown.

Tritt tells the story of how the Naugatuck Chemical Company became not only the first customer of a production model fiberglass sports car, but acted as a partner in its development and promotion. Author Daniel Spurr interviewed Bill about this unique event for his book titled, "Heart of Glass," the story of the birth of the fiberglass industry in postwar America. Bill Tritt recalled...

"At this critical point in Glasspar's growth, the story becomes one of great serendipity and plain luck. The Korean War dealt us a near mortal blow. We suddenly were unable to obtain polyester resin because it was all going to aircraft and other military products. Our purchasing history was laughable, as was I in my fruitless search for suppliers. Then, strictly by chance, I saw a notice of the opening of a new chemical company in a warehouse in South Los Angeles. I had never heard of the company, Naugatuck Chemical, although it turned out to be a division of U.S. Rubber. I didn't know what the warehouse was for, but ... I went inside and found a personable young man named Bud Crawford, who informed me that the warehouse primarily handled shipments of polyester resin from Connecticut. Less than twenty-four hours later, Earle Ebers from Naugatuck, a chemist and devoted proponent of fiberglass reinforced plastic, arrived in California, came to the Glasspar plant, and committed Naugatuck Chemical to sending us an immediate supply of their trademarked resin; Vibrin."

Naugatuck immediately sent him plenty of Vibrin resin. Most importantly, in order to ensure a "first" of national magnitude, the Chemical was quick to order up their very own G2 sports car.

The plan was to use the first-of-its-kind sports car to promote Vibrin to the auto industry. Dr. Earle S. Ebers, from the Naugatuck Chemical not only assisted in the construction of the fiberglass body, he actually drove the finished car all the way home to Naugy from California! This was the first cross-country promotional tour of a production-model fiberglass bodied sports car; destination: Naugatuck, CT!

"At this time, Earle Ebers went up to Naugatuck to meet with George Vila, who was the General Sales Manager, and John Coe, who was the Vice President. They both agreed that Naugatuck Chemical would subsidize the construction of four prototype cars, which was the amount Tritt wanted to justify setting up the bucks and molds. They also agreed to send Earle out to Costa Mesa to work on the first four models and to oversee the operation."

The term "buck" in this usage refers to the wooden forms created to use as a guide over which the fiberglass can be formed.

Ordering four of the G2s ensured their status as "production" cars, and so Glasspar and Naugatuck became joined at the hip in the effort to make production-level fiberglass-bodied sports cars a reality. In the photos you are seeing the very first body being built from the production molds.

"Teaming up polyester plastic and fibrous glass has been called by many in industry the most significant development in new materials in the past decade. One of the reasons is its intriguing possibility as a material for the manufacture of automobile bodies. Tough, dent-proof, easily formed by low-cost methods, impervious to rust and chemicals, the polyester plastic-glass fiber combination seems to have all of the properties needed to make auto bodies more serviceable and durable. A significant step in this direction was made early this year when the Glasspar Company of Costa Mesa, California, placed a body of this type into production. The polyester plastic they used is the familiar Vibrin manufactured by our Naugatuck Chemical division. Dr. Earle S. Ebers, sales manager for Vibrin plastic, worked in close cooperation with Glasspar during the initial stages of production. The first body was mounted on a special frame with a super-charged engine. It was purchased by Naugatuck Chemical and driven by Dr. Ebers on a 3000 mile cross-country road test covering 20 southern cities to see how well it would withstand road service. Its performance exceeded even the hopes of the most optimistic."

Excerpt from: "Us," 1952, Naugatuck Chemical’s U.S. Rubber Magazine trade publication.

Naugatuck's G2 was named the Alembic I, and was also showcased at the Philadelphia Plastics Exhibit in 1952. The name was chosen because Naugatuck Chemical was obviously a chemical company first and foremost. In chemistry, alembic refers to equipment involved in the distillation process.

"And so, with great excitement, enthusiasm, and the backing of a large company, the Glasspar production sports car was born, the Alembic I. Bill Tritt, Glasspar, and Naugatuck Chemical pressed forth, and to the delight of all, LIFE Magazine published the article in February 1952 and the world of fiberglass sports cars was never the same. But the adventure with the Alembic I sports car was just getting started. A cross-country trip was planned with media stops at every city - and this was in the dead of winter! How would the fiberglass sports car fare? What public reaction would greet the car and entourage at every city?"

The outrageous marketing idea worked incredibly well; not only LIFE Magazine quickly featured the car in a story, so did the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and many auto trade magazines. In the photos, you can see many of the promotional photos that appeared in LIFE and other newspapers and magazines.

Bill Tritt's son Matthew related many interesting anecdotes about his famous dad, including...

"The thing about dad that made him such a standout was his “eye”. There were plenty of guys getting into building with glass in the late 40’s/early 50’s, but very, very few of them had such a great feel for what looked “right” and were able to translate a vision into a good, finished product. I guess this is why there’s a G2 in the Smithsonian and why Glasspar was far and away the most successful producer of fiberglass boats up to 1960. He had a long list of “firsts” to his credit."

https://barnfinds.com/brill-tritt-the-man-behind-glasspar/

Indeed, and with Bill's help, a chemist turned promoter from Naugatuck also added to our town's list of "firsts" with a cross-country trek in an open sports car during the cold of winter. Despite the challenging weather, Earle Ebers, Tritt, and everyone at Naugatuck Chemical were extremely aware of the upcoming appearance of the G2 in the February 1952 issue of LIFE magazine. The timing was perfect.

"We had to make it clear, pictorially, that this was a car body that was different from any other car body you had ever seen. ... before the car was painted, the body was actually translucent. That did it. It lit up all kinds of ideas ... about how we could lower the body over the car and light it from underneath."

In the photos you can see the images that appeared in LIFE Magazine featuring the translucent G2 body, illuminated from beneath for an eerie Xray effect. The article in such a popular national magazine was just what Naugatuck needed. They intended to debut the Alembic I in March of 1952 at the National Plastics Exposition in Philadelphia. Capitalizing on the public awareness created by the LIFE magazine feature, they came up with a plan to make an even bigger noise. Dr. Ebers wanted to prove that the fiberglass-bodied G2 was a viable product that could be driven safely, so he decided to tour it all the way across the country to the exposition - from California to Philadelphia! In the photos you can see some of the stops he made and despite the freezing weather, the turnout of curious press and local officials.

Christmas in 1951 might be best remembered for giving us the gift of the very first fiberglass-bodied sports car, thanks to Naugatuck Chemical and a visionary boat-maker from Pasadena.